Today, I’m providing a casual look at the process of emending a work.

Emending is the process of making correcting changes to a work. (As opposed to amending which is adding to or altering a work in order to improve its contents). One significant difference is that emending isn’t designed to change the context or content of a work. Emendation instead strives to fix errors and in the case of the Santayana Edition, reverse edits made to an original work.

According to Mary-Jo Kline and Susan Holbrook Perdue, there are two forms of emendation, overt and silent.1

What does this mean to the average reader? First, it explains all of the words in [brackets] that show up in quotes. These are overt emendations which are indications of items added to a quote by an author or editor. This type of clarifying is commonplace in news and other writing. One such clarification is actually a comment on the text editing itself. “[sic]” at the end of a quote designates that the text appears faithfully including any errors.

You may be thinking, “Well, now that we know about overt emendation, what about this questionable ‘silent’ emendation?” Silent emendation is the tool employed by scholars making fixes to a work that aren’t intended to change any content (even to add context or clarity). Common situations include quotes with improper capitalization or a misspelled word. You might think, “I can make the correction, and nobody needs to know my ‘expert’ evidence had a typo. Right?” Wrong.

Scholars cite sources when working on research because it provides a basis for validity (and separates research from punditry). The same is true with emendations. By noting changes, readers have the opportunity to decide if something is important. Especially with silent emendation, make sure to provide a listing (either in a footnote or as an appendix) showing the changes made. This adds credibility to work, and helps to establish an author as someone with real academic skills.

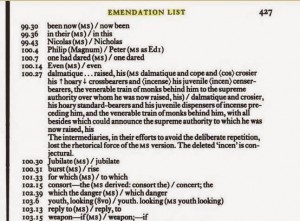

One of the ways to record changes is by employing an Emendation List. In its simplest form, this is similar to a bibliography, works cited, or other academic list. Each entry includes a reference to where the text is (page number.line number), a snippet of the text, a demarking punctuation (commonly a bracket “]” or slash “/”), an edited version of the text, and if necessary a reason for making the change. If this lacks clarity, let’s look at an example. Below is a screenshot of an emendation list included in a recent edition of The Abbot by Sir Walter Scott.2

The editor, Christopher Johnson, provides examples of the various changes one might make through silent emendation to a text. The note at the bottom of 100.27 is an example of a situation where the change might not make sense at first, so Johnson explains his rationale for it.

Including the particular version of the text used is essential. Notice, in the instructions above, the reference includes both a page number and a line number. You may not be familiar with line numbers as references, but they tell a reader exactly which phrase is referred to. Typically, they do not work across editions (thus knowing the version is critical), but it can be a significant difference if the same phrase appears repeatedly on a page (Can you imagine trying to figure out which “. A” someone might be talking about?).

One of the most highly regarded qualities in academia is ethical standard. If readers cannot count on work to be accurate (and verifiable). Scholars achieve this standard by making sure that facts are vetted, and then being transparent about how facts are used. In doing so, researchers keep themselves out of legal and academic trouble and their work out of the garbage can. There are enough battles to fight these days about scholarship. Don’t compound them by clamming up about how you get to conclusions.

Note: This text originally appeared November 4, 2014 in another form on A Historian Finding His Way (http://historianfindingmyway.blogspot.com/) under the title “Emendation: The Incomplete, Abridged, and Generally Just-a-Primer Lay Persons Guide.”

References:

- Mary Jo-Cline and Susan Holbrook Perdue, A Guide to Documentary Editing, 3rd ed. (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press), 145.

- Christopher Johnson, ed., The Abbot by Sir Walter Scott (Edinburgh, Scotland: Longman, 1820; Edinburgh University Press, 2000), 427. Photo from Google Books.

Published by: Ethan Chitty

Published on: Nov. 11, 2014