To Rosamond Thomas [Sturgis] Little

To Rosamond Thomas [Sturgis] Little

Via Santo Stefano Rotondo, 6

Rome. October 16, 1950

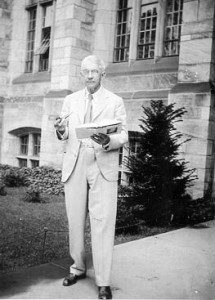

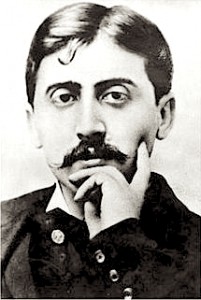

You said in your last letter that you would like to know Cory: but you might not like him at all. However, he is by instinct a lady-killer and ingraciates himself into some women’s good graces in a surprising way; but has become less attractive (and deceptive) with middle age and cannot do the elderly gentleman as well as he did the young intellectual. He is intellectual, but strangely ignorant of literature and history, except in spots, where he has taken an intense interest in certain authors, especially Walter Pater in his youth and Proust (read in translation) in recent years. He took in this way to the most technical of my books, “Scepticism and Animal Faith”, and at 22 wrote a remarkable paper on it, which was the source of our acquaintance. He now understands my whole philosophy, but does not inwardly accept it, and really does not help me very much, except by finding fault (he is very “cheeky”) with my style when I make a slip, which after all proves that he appreciates it when it goes properly. But his chief virtue for me is that he is extremely entertaining; and also, now, that he understands the new school of poetry and English philosophy he also understands Catholic philosophy in places (where it is wrong) because it contradicts modern philosophy (which is wrong at that point also). He would have made a capital actor, is a most amusing mimic, and has a bohemian temperament, spends money when he gets it, and never thinks of the future.

From The Letters of George Santayana: Book Eight, 1948-1952. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2008.

Location of manuscript: The Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge MA