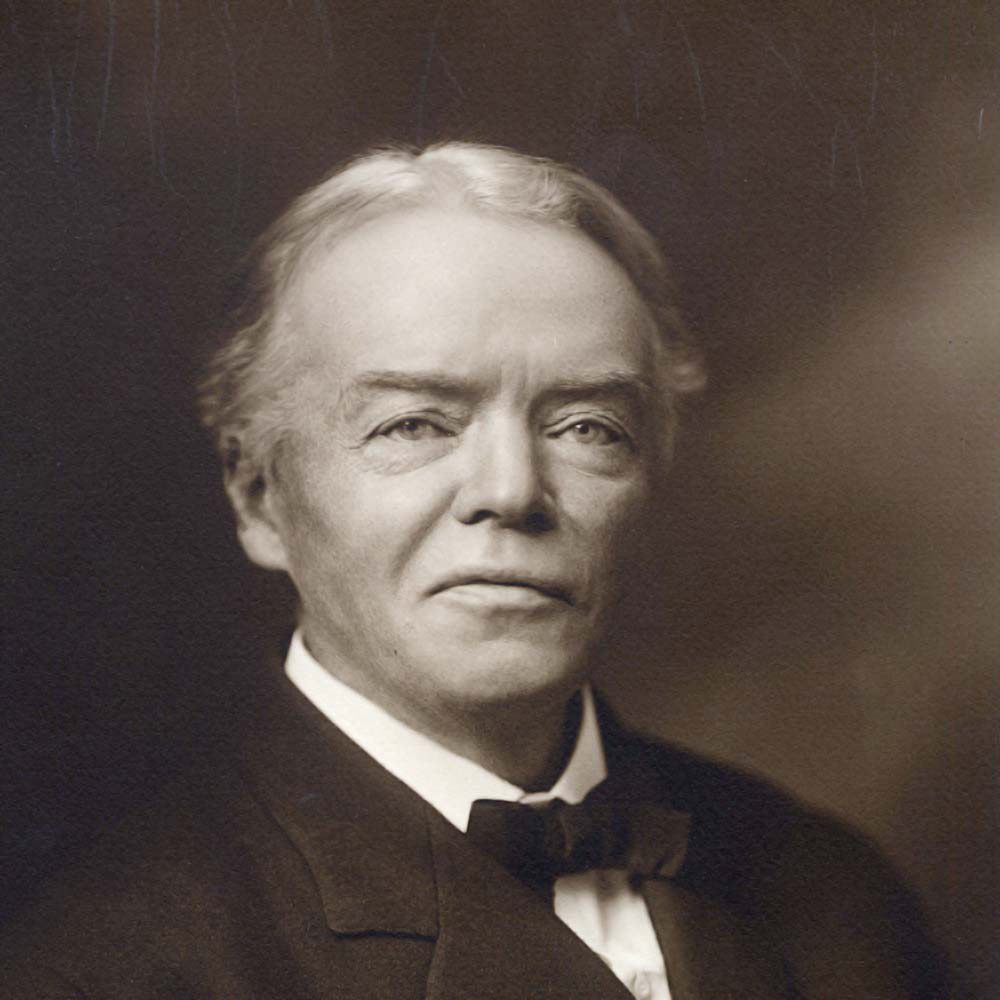

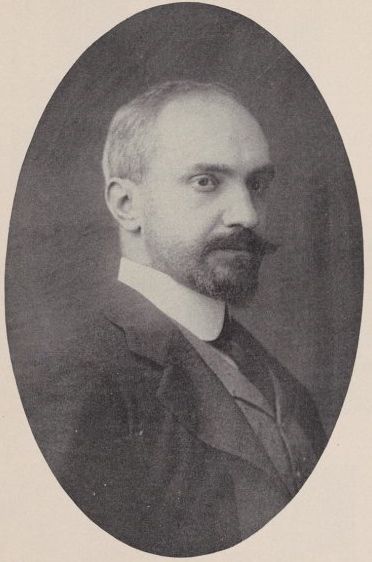

To Charles Augustus Strong

To Charles Augustus Strong

Brookline, Massachusetts. April 19, 1900

I am delighted beyond measure that my little book should please you. Thank you very much for all you say. It encourages me very much, coming from a person of your solid judgment and religious nature and education. If you find my book good, it can’t be rotten. But I must attempt to answer your criticism, so as to set myself right both with you and with my own conscience. When I said that religion should give up its pretension to be dealing with matters of fact, I meant, as you doubtless felt yourself, that the religious machinery (gods, hell, heaven, grace, sacraments etc) was not in the plane of fact but in the plane of symbols. But symbols are symbols of fact; and in a sense poetry deals with matters of fact, and the better and more poetical the poetry the more real and fundamental the facts with which it deals. It is not artificial in the sense of being arbitrary. It is a representation of reality, according to the requirements of a part of reality, the human imagination. And yet there is a plain sense in which it is right and obvious to say that poetry does not deal with (I should have said, perhaps, does not contain, does not constitute) matters of fact. Apollo is not a fact in the same plane as the sun: yet the religion of Apollo “deals with” the fact “sun”. Otherwise the religion of Apollo would be impossible; it would have no basis and no subject-matter. So that all I mean by relegating religion to the sphere of poetry is to distinguish, as we should all do in poetry, between the reality represented and the fiction by which that representation is made. Painting does not deal with flesh and hair, but with pigments; yet by its manipulation of those pigments it represents, and, if you like, deals with, hair and flesh. Possibly the whole ambiguity might be removed by saying deals in, instead of deals with. But my book was not meant to be a creed, even for skeptics, and its definitions are not meant to have theological precision. They are “thrown at” ideas.

You can’t sum up the moral values of the parts of the Universe and say the result is the moral value of the Universe itself. For these moral values cancel one another and disappear into merely physical energies when you trace them back to their source. The good and evil in the world are not the world’s merits and demerits, because by the time you have traced them back to the general laws from which good and evil alike flow, the laws have forfeited those moral characteristics. I disagree, then, with what you say about the credit for what is fair and good being due rather to the Universe than to us. It is as if you said vision belonged rather to the Universe than to the animals in it, because of course the Universe gave the animals eyes, and not they to themselves. The Universe deserves no credit for our virtues until it acquires them—until it becomes ourselves. When the sympathy with moral ends begins to be a principle of action, moral values arise; there are none in the mere conditions of goodness, and the rain and the corn and sunshine are not moral objects. To regard them as such is really to make them gods; it is mythology; and to my mind your awe- inspiring, amiable, sympathetic and admonishing Universe is a mythological object. I value it as such; as such it is a religious idea, and a true one; but it is not a matter of fact.

From The Letters of George Santayana: Book One, [1868]-1909. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2001.

Location of manuscript: Rockefeller Archive Center, Sleepy Hollow NY.

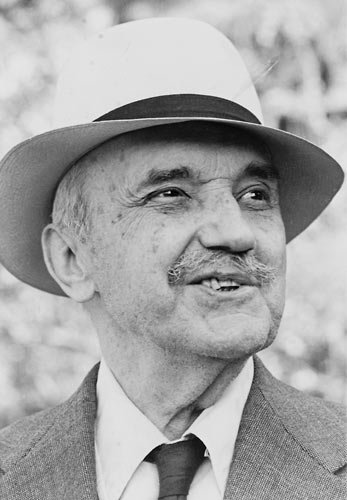

To Josiah Royce

To Josiah Royce