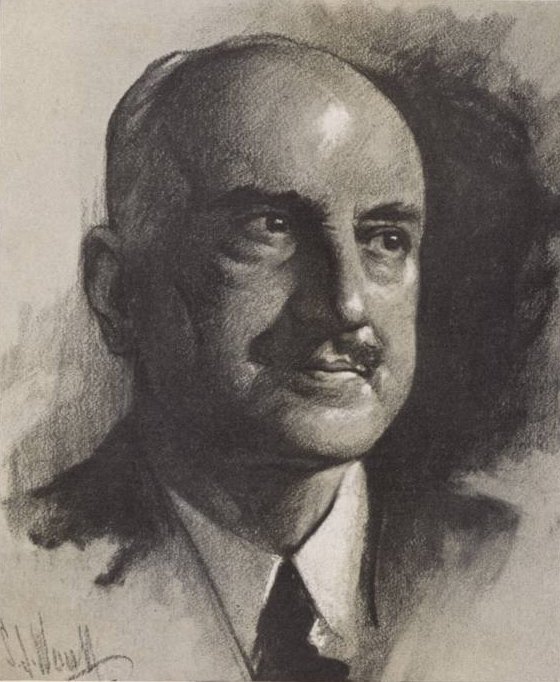

To Van Wyck Brooks

To Van Wyck Brooks

C/o Brown Shipley & Co. 123 Pall Mall, S.W.1. London

Rome. May 22, 1927

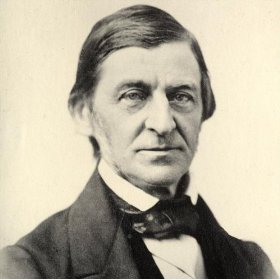

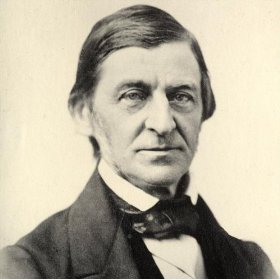

Although I am not sure whether I owe the pleasure of reading your book on “Emerson & Others” to your initiative or that of your publishers, I would rather thank you personally for it, because I have one or two things which I should like to say, as it were, in private. Your pictures of Emerson are perfect in the way of impressions: not that I knew him (he was dead, I think, when I first reached America, aged 8); but that, whether true to the fact or not, they are convincing in their vividness. But just how much is quoted, and how much is your own? Am I to believe—I who haven’t read the Journal and know little of the facts—that Emerson was such a colossal egotist and so pedantic and affected as he seems on your pages 39 and 40? Or have you maliciously put things together so as to let the cat out of the bag? Sham sympathy, sham classicism, sham universality, all got from books and pictures! Loving the people for their robust sinews and Michaelangelesque poses! And for the thrill of hearing them swear! How different a true lover of the people, like Dickens!

You apologize because some of your descriptions applied to the remote America of 1919: I who think of America as I knew it in the 1890’s (although I vegetated there for another decade) can only accept what I hear about all these recent developments. On the other hand, when you speak of the older worthies, you seem to me to exaggerate, not so much their importance, as their distinction: wasn’t this Melville (I have never read him) the most terrible ranter? What you quote of him doesn’t tempt me to repair the holes in my education. The paper I have most enjoyed— enjoyed immensely—is the one on the old Yeats. His English is good: his mind is quick.

Why do the American poets and other geniuses die young or peter out, unless they go and hibernate in Europe? What you say about Bourne (whom again I haven’t read) and in your last chapter suggests to me that it all comes of applied culture. Instead of being interested in what they are and what they do and see, they are interested in what they think they would like to be and see and do: it is a misguided ambition, and moreover, if realized, fatal, because it wears out all their energies in trying to bear fruits which are not of their species. A certain degree of sympathy and assimilation with ultra-modern ways in Europe or even Asia may be possible, because young America is simply modernism undiluted: but what Lewis Mumford calls “the pillage of the past” (of which he thinks I am guilty too) is worse than useless. I therefore think that art, etc. has a better soil in the ferocious 100% America than in the Intelligentsia of New York. It is veneer, rouge, aestheticism, art museums, new theatres, etc that make America impotent. The good things are football, kindness, and jazz bands.

From The Letters of George Santayana: Book Three, 1921-1927. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2002.

Location of manuscript: The Charles Patterson Van Pelt Library, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

To George Washburne Howgate

To George Washburne Howgate