To Daniel MacGhie Cory

To Daniel MacGhie Cory

Rome. April 10, 1933

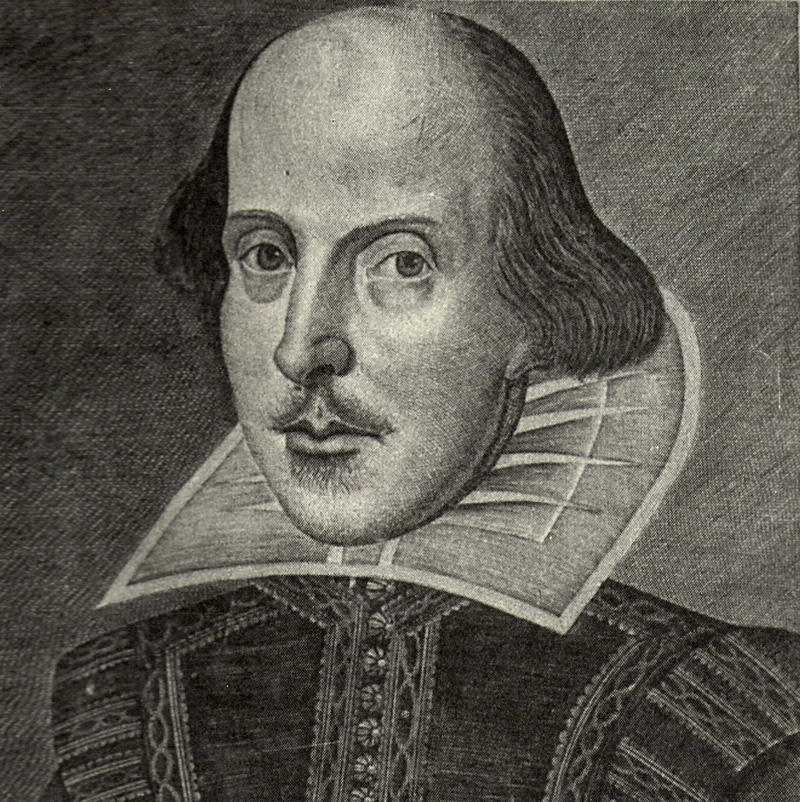

Logan Pearsall Smith has sent me some sugared hay of his own about “Reading Shakespeare”. It is pleasantly written, except where he feels impelled to speak in hushed superlatives about Shakespeare, as if he were speaking about God. The need of possessing the biggest poet in the world puffs him out; and there is over-interpretation in the wake of Coleridge and Lamb; but he mentions a naughty American professor Elmer Edgar Stoll who seems to have seen light by the Mississippi, and goes to the other extreme.

Part II (18 chapters) of the novel is now finished and typed, and I am busy revising the beginning of Part III in which your friend Mario makes his appearance, aged 16. I am beginning to feel encouraged about finishing this endless task. It is not as clever and amusing as I meant to make it, but it turns out deeper and more consistent than I had suspected. There is a hidden tragic structure in it which was hardly foreseen but belongs to the essence of the subject, the epoch, and the dissolution of Protestantism.

From The Letters of George Santayana: Book Five, 1933-1936. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2003.

Location of manuscript: Butler Library, Columbia University, New York NY.